Publisher James J. Conway on five years of Rixdorf Editions

There is a tree in Berlin. Well, in truth there are lots of trees in Berlin (‘it’s so green!’ marvelled my father on the ride from the airport when he visited Berlin for the first time, finding it to be nothing like the grim, grey city of Cold War reputation).

There is a specific tree in Berlin that I am thinking of. It’s in Neukölln, in a confusing slanted grid of streets off a canal not far from where I live. Around eight years ago I was walking back from the canal-side Turkish Market; it was April, early afternoon, sunny. From a corner I was struck – not just struck, truly transfixed by the sight of a tree in new green growth. There were numerous trees on both sides of the street in a similar state of springtime rejuvenation, but there was something about the way the sunlight caught this particular tree, turning its freshly sprouted leaves into little lanterns, rare gems sequinning the lambent air to form a veil between dimensions, as it seemed to me. As I stood there I heard the morning of the world, I saw ragas in leaf and light, I felt beauty as deep as time. All this from a tree on a footpath in the middle of the city.

It was only when I first read the 1908 essay Die Schönheit der großen Stadt (The Beauty of the Metropolis) by Jugendstil architect August Endell that I found the words to match what I had seen, the music of his prose proving an uncanny echo of my experience. I had a profound response to the wonder, the urgency with which he described the recurring natural phenomenon of spring growth. And it was not just these fleeting aesthetic impressions of city life that his brisk study addressed, but so many questions about identity, culture and belonging that had been preoccupying me, as someone privileged enough to start their life anew on the other side of the world as a matter of choice. Endell vigorously renounced delusional nostalgia, nationalist chauvinism, völkisch pathos. Who gets to enjoy art, music, literature, cities, nature, the sights and sounds around us? Anyone, he argued, with the capacity to appreciate them.

I had so many of these flashes of recognition, moments of collapsing time, in what became an obsessional phase of reading texts from Germany’s Wilhelmine era – where the 19th century met the 20th, where reaction met revolt. I discovered surprising cultural progress in defiance of a conservative official culture, an astonishing wealth of both fiction and non-fiction, almost entirely untranslated into English, which I felt deserved greater exposure. I found very little present-day commentary to corroborate my findings about the era, but this very absence just made it more alluring, extending a promise of something to be discovered fresh, unburdened by multiple layers of interpretation. I am an autodidact in this field, but I like to think I’m not a sloppy autodidact; I set myself the task of learning as much as I could about the history and culture of the period.

From my day job of commercial translation I had already been thinking about moving into literary work, and the longer I dwelt with these books and the era from which they emerged, the more I felt that the best way to honour them would be to present original titles, translated, with commentary. Printed books, not digital; shorter works, not doorstops that would overburden the potential reader’s curiosity. I had just gained German citizenship and in my own weird way, I wanted to give something back by highlighting a positive yet neglected chapter in my adoptive country’s history. Perhaps if I had been more patient I could have pitched the idea to someone with more publishing experience than I had, which is to say any at all. On my own bookshelves there were numerous translated books issued by small presses that were rediscovering, newly translating and thoughtfully contextualising works of the past, and it was to their example that I aspired. Closer to home I was highly impressed by a small English-language press here in Berlin, Readux, the brainchild of Amanda DeMarco, who gave me valuable advice and encouragement. In the face of my beginner’s enthusiasm she also wisely suggested I keep an end point in mind.

In thrall to obsession and with the utterly unwarranted confidence of a frequent flyer who decides ‘I bet I could pilot one of these things!’, I embarked on the arrant folly of starting up a small translation press from my Neukölln apartment: Rixdorf Editions. I worked with designer Cara Schwartz to developed an identity and a cover format based on imagery of the Wilhelmine era; her studio was just around the corner from ‘my’ tree, which I took as a good sign. As I furiously finished off the words to go in between the covers, we found a printer in Poland, and the day the proofs of the first books arrived was joyous – finally, the thing in my head had become something I could hold in my hands. And on the charged date of 9 November, five years ago today, we launched the first two Rixdorf titles in the lovely Curious Fox bookshop on unlovely Flughafenstrasse.

Call it wilful presumption, but I would like to claim ‘Bohemian Countess’ Franziska zu Reventlow as the presiding spirit of this whole publishing experiment, and I was hugely proud to issue the debut English translation of her work as the first Rixdorf fiction title. Originally published in 1917, shortly before the author’s death, The Guesthouse at the Sign of the Teetering Globe opens with the title story, an extended analogy for the collapse of the old European order which the author foresaw but wouldn’t live to see. In Germany, Reventlow is primarily remembered as something of a slumming aristo party girl, but in both her deployment of irony and her vision of what came after her, she seems far more a creature of our own era. I had another moment of collapsing time when I realised that the ‘correspondence club’ she invents in that title story was essentially a premonition of present-day social media. Reventlow’s surreal tales render bizarre incidents and characters in a crisp, understated, unornamented style which is closer to reportage, an intriguing contrast to the elevated, lyrical prose with which Endell captured the material world.

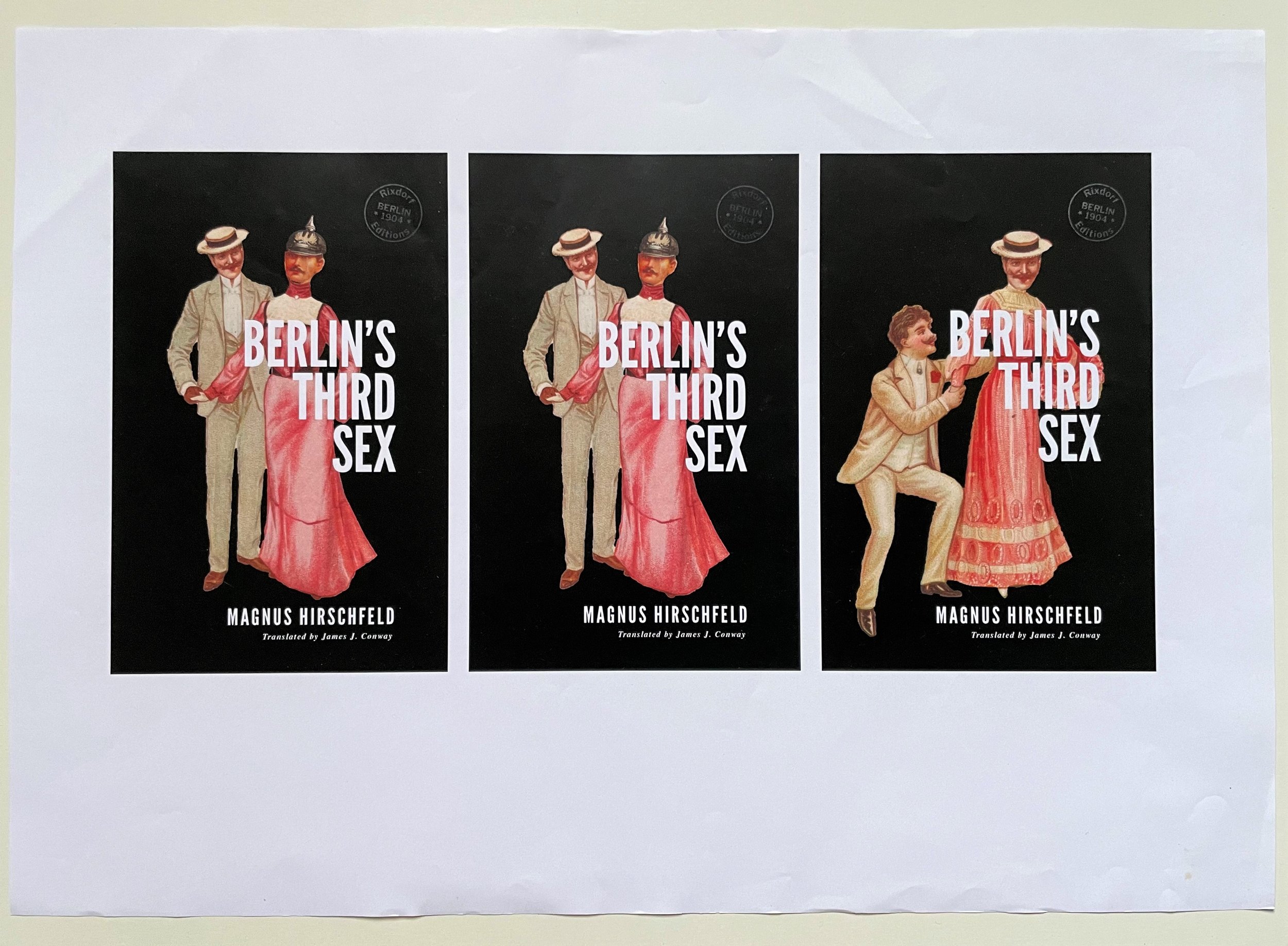

Time collapsed again when I first read what would become the other launch title: Berlin’s Third Sex. Author Magnus Hirschfeld bears witness to an amazingly diverse and increasingly confident queer subculture in the German capital and so much of what he depicts sounds like the end of the 20th century, rather than its outset. Or – now. For example, Hirschfeld describes a telegraph service which allowed the user to find temporary companionship based on a set of criteria, essentially the hook-up app of its time. His terminology is not fixed, he conflates gender dysphoria, same-sex attraction and intersex characteristics, but crucially he presents the people he talks about as just that – people, rounded individuals, far more than the sum of the pathologies or ‘degeneracy’ projected onto them by the majority culture. This became – by far – the best-selling and most widely discussed Rixdorf title.

The Times Literary Supplement ran Anna Katharina Schaffner’s full-page review of the first two titles in March 2018 which made me think – maybe I really was on to something? I was impatient to share the riches I had discovered, and that spring brought two more titles, including the seasonally appropriate Endell. In another edition I compiled two works, 20 years apart, by the winningly named Anna Croissant-Rust. Issued on the eve of the First World War, her book Death was a concept album of mortality, a suite of deft sketches plotting final moments in a style that was paradoxically filled with life. But further back in her bibliography, in the early 1890s, I discovered a wild, unclassifiable rush of fragmentary writing, jagged and uncompromising, whose title of Prose Poems was the only prosaic thing about it. Decades ahead of its time, this was one of the hardest works to translate, because I wanted to honour the alien quality in the writing and not surreptitiously unravel its knotty oddities. Gratifyingly, Electric Lit highlighted this edition as one of its ‘8 Groundbreaking Experimental Novels That Are More than 100 Years Old’. Engaging with Anna Croissant-Rust’s work has given me even greater respect for translators of poetry.

In promoting the works I always foregrounded the authors themselves; compared to them I felt my own story was just not that interesting. Even writing this I feel the constant urge to divert attention to the books and away from my own experience. But in discussing Rixdorf the question of how someone from Sydney ends up in Berlin translating obscure German literature inevitably arose, as it did in September 2018 when I was interviewed live on radio by Australian broadcaster (and official national living treasure) Phillip Adams. His voice issuing from my parents’ radio was among my earliest memories, and I thought of how excited my mother would have been if she were alive to hear. It was a surreal moment, like the time Australian children’s TV legend Humphrey B. Bear turned up for my birthday (or my sister Madeleine’s; neither of us can remember). I completely lost my Scheiße. If you are not Australian I’m not sure I can adequately convey how life-changing it is to have Humphrey B. actual Bear at your birthday party.

Issuing four books in little over six months had left me wrung out, but in a moment of folly I decided that 2018 needed another dispatch from Wilhelmine Germany: We Women Have no Fatherland. Much as Hirschfeld had picked up on the modish buzzword ‘third sex’, a term featuring in dozens of titles in the Wilhelmine era, author Ilse Frapan was one of numerous writers of the time focussing on the new figure of the female student. At the close of the 19th century, her youthful protagonist is barred from university in her native Germany and goes to study in Zurich (as Frapan herself did), painfully aware of the precarity of her status as an independent woman (as Frapan certainly was). Her tempestuous passions swell into dreams and visions, into saintly exaltation. But this edition was born under a bad star; as convinced as I was of the author’s message, the style jarred somewhat, and I should have respected my initial reservations. I’m going to be real with you here: that thunderous title was a large part of why I wanted to translate it. Even the phase of the process that I usually enjoy most – the research – turned up little that seemed truly noteworthy. It was the last cover with Cara Schwartz and we disagreed on the design and ended up with a compromise that pleased neither of us. My promotion was lacklustre, the response correspondingly muted.

And it was with this of all titles that I decided to go to the Frankfurt Book Fair with my UK distributor in October 2018. Encountering the bewildering immensity of the world’s largest publishing event, I cursed my decision to wear smart yet uncomfortable shoes as I wandered the kilometres of stands. I met up with my contact from the Polish printer. ‘Your books are very … particular,’ he noted. ‘Have you ever thought about publishing bilingual children’s books? There’s a big market for them.’ The thing is, he was right. I knew from going to the library with my stepdaughter that there was a gap in the market for good bilingual children’s books, and if I had approached publishing as a purely commercial undertaking, perhaps I might have started there, or at any other point which offered greater prospect of sales. But that’s not how obsession works. What I aspired to instead, in my very modest way, was something like Wakefield Press and Seagull Books had established; in Frankfurt I got to meet their respective creators, Marc Lowenthal and Naveen Kishore. The standard opener in all these encounters was ‘What are you doing here?’ While my interlocuter was inevitably extending a simple, friendly enquiry, I – with galloping imposter syndrome – italicised the pronoun in my mind: ‘What are you doing here?’ And, honestly, what was I doing there? I was starting to feel a bit like a lobbyist for an industry no one has heard of, or an agent for the dead – certainly not a professional publisher. Wherever my place was, it wasn’t here.

That year’s centennial remembrance of the end of World War One inevitably highlighted the martial side of the German Empire. But as I argued to anyone who would listen, it was also the birthplace of modern gay identity, a crucible of feminism, an important site of modernist endeavour and progressive thought. Consider the eco-conscious counterculture: it was a way of living born not on the West Coast of the USA, but rather on the frigid cobblestones of late 19th-century Munich. Cafés in German cities witnessed strategies of personal anarchy and radical cultural output. A lively network of bohemians did exactly what bohemians should: drink, argue, sleep around, defy rules, take drugs, hatch plans. All of this was driven by self-willed eccentrics and fearless polemicists whose impatience for a better world lent the avant-garde an energy to match the dynamism of German industry. Bookended by war, the German Empire offered numerous fruitful alternatives in between.

But why – I asked myself at numerous points over the last five years – was this such a productive era for experimentation? Apart from the opportunities provided by the phenomenal pace of change in the era, it occurred to me that the German Empire was, as perverse as it sounds, just repressive enough. Which is to say it was a semi-autocratic state with a reactionary mainstream culture so there was definitely something to rebel against, but it wasn’t so repressive that it silenced radical voices entirely. Yes, some writers were censored, fined or even jailed for lèse-majesté, blasphemy, obscenity and other infractions, but it’s remarkable how many more weren’t when you consider the extremity of their positions. The countercultural vigour of the age, it appears to me, dwelt in this narrow gap between widespread antipathy and blanket repression.

From this gap, writers considered the most fundamental questions of the day. Few were as pressing or destructive as antisemitism, which at the time was shifting from a centuries-old, predominantly religious hatred to something even more sinister, the politicised race hate of which Germany and France were the main centres. Austrian author Hermann Bahr, who had experienced his own trajectory from prejudice to enlightenment, took a pan-European approach to this issue in 1893, interviewing figures throughout the continent – an entirely new concept in German letters. In 2019 this became the sixth Rixdorf book.

Bahr’s interviews not only show us the roots of 20th-century horrors, they also expose the workings of prejudice and populist politics as a whole, the way in which minorities – whether that’s Jews or other ethnic groups, migrants or asylum seekers – serve as convenient alibis for inequality and exploitation in ways that are still depressingly clear to us now. Multiple German political parties of the time traded solely in hatred of Jews, and among their ranks we find unhinged, hateful, post-truth demagogues of a type that is, again, all too familiar.

Yet for all its headline insights, Antisemitism was also a milieu study benefitting from Bahr’s acute eye for passing detail and the nuances of character. But even my appetite for research was exhausted by the wealth of references, which left me longing to return to fiction. This led me to translate The Nights of Tino of Baghdad, a short work by Else Lasker-Schüler, a figure who had become increasingly important to me, and slip it out on PDF even before releasing the Bahr (with the first of four covers by Svenja Prigge). In early 2020 I went to Wuppertal for an exhibition of Lasker-Schüler’s life and work. To visit the author’s home town, to view the artefacts of her life was a moving experience. Meanwhile the Rhineland Carnival season was starting up, and when I reached the old town of Düsseldorf it was heaving with people. It would be the last time I experienced crowds for a while.

I had started 2020 with a fiction project which was almost at the final draft stage, and even had a cover, but once we went into lockdown I reflected on the quality and found it wanting. Chastened by the Frapan experience, I decided I didn’t want to put out something I didn’t entirely believe in, and shelved it. I won’t beat myself up for not publishing anything in 2020. Like everyone else, I was just trying to stay sane and get by, and the enormity of events made the concerns of a tiny niche press seem even less significant.

But I still hoped to emerge with something new, and I picked up a title that had been on my mind for some time – Papa Hamlet by Arno Holz & Johannes Schlaf. Its pessimism is relentless, shading into nihilism, and it plays out almost entirely in a single space that the inhabitants seem unable to escape; one of them is even afflicted with a lung disease. What better project to make those long lockdown nights simply fly by?

It shouldn’t even have been surprising that this 130-year-old book had captured this fraught moment. It had already foretold modernism – in its fragmentary exposition and psychological extremes – while in its ostentatious appropriations, caustic irony and play of identity it even offered something of the postmodern, almost a century ahead of time. It emerged from and yet transcended the Naturalist movement, which was also the platform from which Anna Croissant-Rust launched her experimental early works, and once again I was the weird guy saying ‘everything you thought you knew about something you probably haven’t given much thought to is wrong!’.

Drawing out the numerous fascinating ways in which to approach Papa Hamlet, especially its origins in the authors’ bohemian Berlin lifestyle, led me to visit the sites of the authors’ lives, including the leafy enclave of Niederschönhausen. I cycled through the gardens around the local schloss, filming with my phone, and unsurprisingly ended up with a lot of shaky footage (that Martin Scorsese, I ruefully reflected, must have a really steady bicycle).

This was an increasingly important, and satisfying, part of my engagement with these figures – spending time in locations associated with them, which became places of communion and reflection. I had visited the village on the island of Corfu where Reventlow had lived in the early 20th century, an important inspiration for her fiction, and the Swiss town where her heroic existence met its premature end. Viewing my adoptive home of Berlin through ‘my’ authors’ eyes revealed an entirely different city. I often cycled through Hallesches Tor, now an area dominated by post-war apartment blocks and an air of neglect, but around 1900 it was a busy hub and, as I discovered through Magnus Hirschfeld, a centre of queer life in Berlin. When I found out that the Wilmersdorf apartment where August Endell wrote The Beauty of the Metropolis had survived the war, I contacted the current occupant who kindly let me visit. And so it was that in the presence of a mildly bewildered child psychologist I stood staring at the wall – one of those huge firewalls that separate Berlin apartment buildings – that marks the start of Endell’s citywide odyssey in the second half of his book. The site in the Tiergarten district where Hermann Bahr began his investigation of antisemitism in Berlin in the 1890s was around the corner from where Else Lasker-Schüler nursed her dying son in the 1920s.

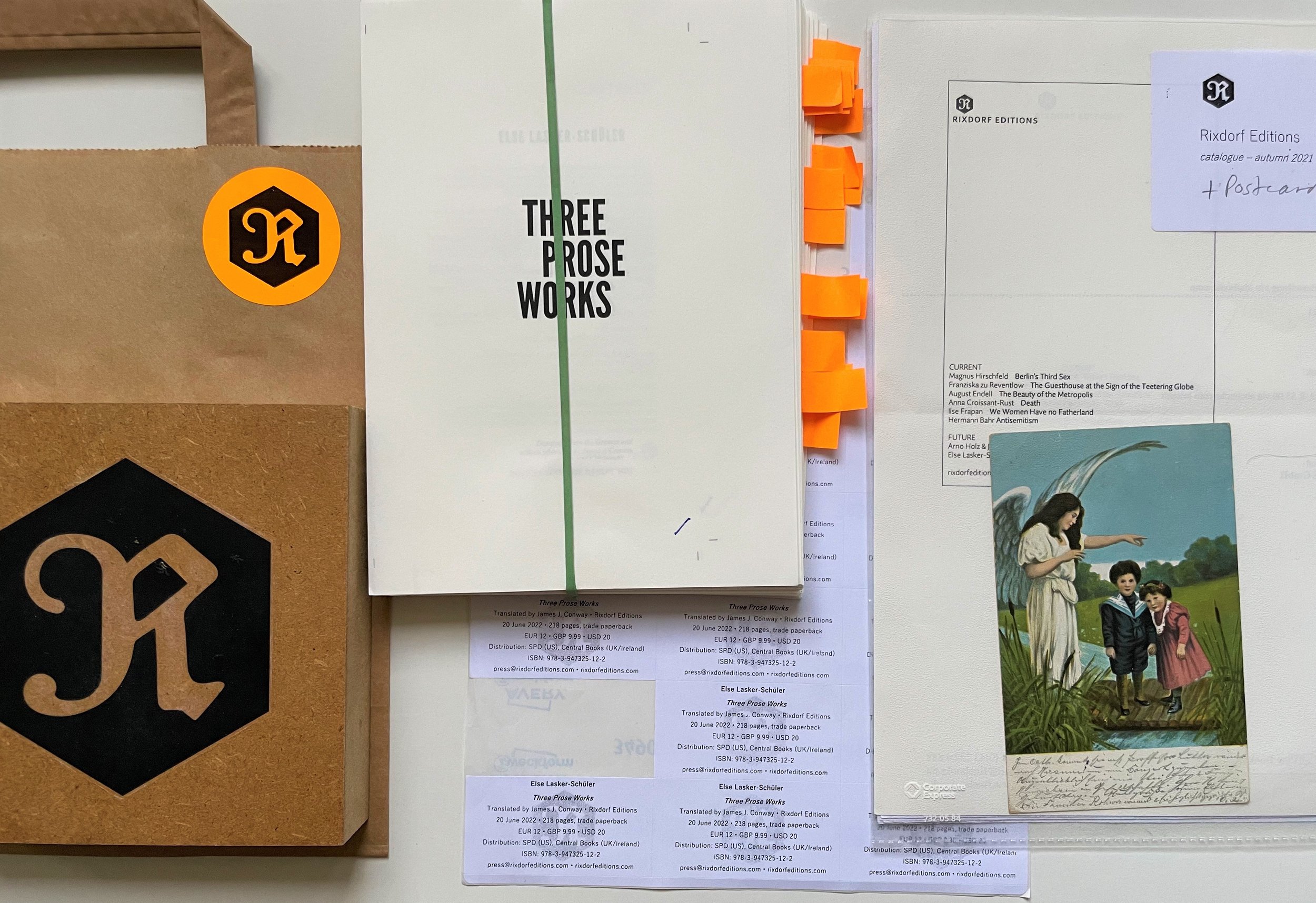

And it was in Lasker-Schüler’s footsteps that I trod once again as I warily emerged from lockdown to see an exhibition of her correspondence in Berlin, on a site next to the Brandenburg Gate where she first exhibited her art. As I reflected at the time, labours of love – such as my engagement with Lasker-Schüler’s life and work – never really end. Picking up on two similarly brief books either side of Tino, I discovered a through-line that I felt justified presenting them together – Three Prose Works. Everything about Else Lasker-Schüler, the life she wrote for herself as much as anything she committed to paper, suggests someone who should be much better known in the English-speaking world, and I can’t account for why that isn’t so. Digging deep into her biography only enhanced my admiration; she was prodigiously connected, and to explore her life is to summon the restless spirit of an entire age. The labour of love goes on, and I am sure this isn’t the last time I will encounter Else Lasker-Schüler.

It is a point of pride that with the publication of Three Prose Works, half of the (admittedly modest) Rixdorf catalogue is by women writers. People like Meytal Radzinski and initiatives like the ‘Women in Translation’ month every August are doing extremely valuable work to highlight and help correct the gender imbalance in translated works. Overall it has been highly encouraging to be in this field at a time when the work of translators enjoys greater appreciation than ever before, even if my authors are not around to see their works reaching an (admittedly modest) new readership.

And although they are long dead, the questions they raised have forfeited little of their relevance. How do you combine the urge to create with the need to make money? (Holz & Schlaf, Reventlow) What does poverty and despair actually look like when you strip it of all romanticism and pathos? (Holz & Schlaf) How do you retain and even celebrate your otherness in the face of the monolithic ethno-state and often violent opposition? (Lasker-Schüler, Bahr) Who gets to participate in education and democratic processes? (Frapan) What place is there for sexual and gender minorities within a dominant culture that questions their very existence? (Hirschfeld) What happens when you take a blank piece of paper and re-imagine literature? (Croissant-Rust) How do we seize aesthetic ownership of our environment? (Endell)

I always say that if I were an eccentric millionaire, I would do nothing but translate works from the Wilhelmine era. It is not just the wealth of ideas and artistic experimentation. It is also that together, they represent a progressive heritage that is worth celebrating, something particularly valuable at a time when basic standards of tolerance, openness and enquiry – which many of us assumed were assured – are increasingly under threat.

Sadly I am not an eccentric millionaire. This was always a naïve endeavour, and not having the time or resources to properly promote the works is a perpetual frustration. Yes, complaining about the difficulties of running a small press is a little disingenuous, because it’s not like anyone ever said ‘you should totally start your own press! It’s super easy and you’ll make a ton of cash’. It’s not, I didn’t. But there have been hugely stressful, sometimes overwhelming setbacks: delivery charges tripling, an entire print run botched, multiple shipments going missing (and may I take this opportunity to say: screw you for all eternity, USPS). Yet of course there were the positives as well: getting picked up for distribution in the UK and the US, thoughtful reviews by engaged writers and, most gratifying, readers getting in touch to say how much they appreciated the books. And in this spirit I would like to say thank you (for all eternity) to everyone who has been part of this five-year adventure, particularly my partner Miles who has provided editorial and moral support from the beginning.

Unbidden, however, the question arises again: ‘what am I doing here?’. I find myself without a path forward, so sadly Rixdorf Editions will be no more after 2022. But labours of love, I remind myself, never truly end, and I know that in whatever form I will keep returning to a period that has already offered endless inspiration, just as I will keep returning to that tree every April.