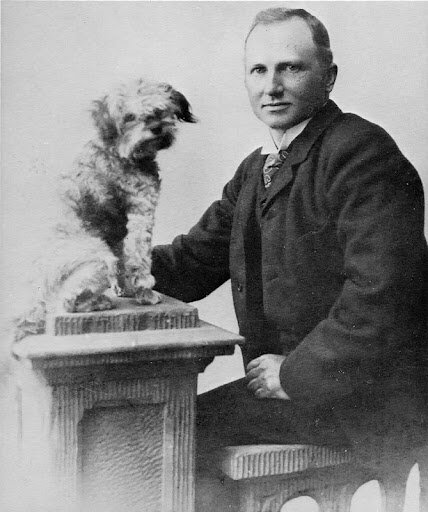

Oskar Panizza and his dog Puzzi

Today marks 100 years since the death of the German writer Oskar Panizza, although his literary production was stilled some time earlier, with the one-time psychiatrist spending the last 16 years of his life in a psychiatric institution.

The Wilhelmine era, as the entire Rixdorf list indicates, offered a wealth of progressive and even radical writing which emerged from a conservative if not reactionary culture. Many writers were subject to censorship on the grounds of obscenity, blasphemy, lèse-majesté, sedition and other categories by which imperial authorities sought to contain unruly elements. Books were sometimes confiscated, publishers fined, but this could also be turned to advantage in the form of publicity. Prison, on the other hand, was rare.

Oskar Panizza, however, paid the highest price of any writer in the Wilhelmine era. While many of his works were subject to censorship, he didn’t so much as step over a line as catapult across it with his play Das Liebeskonzil (The Council of Love). Subtitled ‘A Heavenly Tragedy’, it posited that syphilis had been introduced to the world by the daughter of Salome and Satan via the court of the Borgia Pope, Alexander VI. While this would have been confronting anywhere in 1894, in Catholic Munich where Panizza was living at the time it unleashed what present-day Germans endearingly call ein Shitstorm. And it earned Panizza a year in prison on no less than 93 counts of blasphemy.

But did Panizza (who, by the way, knew a thing or too about syphilis) deliberately provoke this outcome? In the book Banned in Berlin which addresses literary censorship throughout the German Empire, Gary D. Stark suggests that Panizza ‘not only wilfully exploited the notoriety his incarceration brought, but in fact actively courted a confrontation with the authorities as a way of achieving literary fame and success.’ If so, it was a remarkably durable strategy – German director Werner Schroeter’s film version of the play was banned in Austria almost a hundred years later.

Panizza had connections with two of the authors Rixdorf Editions has published. He was close to Franziska zu Reventlow, who wrote for his ‘exile’ journal Züricher Diskussionen, and was also the subject of a flattering profile which Panizza wrote for the same organ. Anna Croissant-Rust, meanwhile, who came into contact with Panizza in Michael Georg Conrad’s ‘Society for Modern Living’, was a sympathetic and supportive friend, visiting him in prison and later on in psychiatric institutions.

A modest selection of Panizza’s highly erratic bibliography has been translated into English. The most readily available are The Pig, translated by Erik Butler, and the The Love Council, in a volume by Peter D. G. Brown which also addresses the controversy around the play and the life of the writer.

There is much more to say about Oskar Panizza and the outer limits of Wilhelmine literary production, but for now perhaps it is better to let the man himself speak. The remarkable document below is one of the last things he ever wrote before his mental incapacitation, and it offers a clipped, clinical account of his life and work. Panizza wrote it in 1904 and submitted it to authorities who were seeking to gauge his state of mind. He refers to himself in the third person throughout and evaluates himself with striking clarity, as though Panizza the psychiatrist were assessing someone who just happened to share his name. Aside from suicidal ideation, the greatest manifestation of his illness is an auditory hallucination and associated paranoid persecution complex, which – analyst cum analysand that he is – he both posits as real and suggests is of pathological origin. By the way, those parenthetical exclamation marks and interjections of ‘(Wrong syntax!)’ are in the original. The German version also reflects Panizza’s idiosyncratic spelling, with words like Pazient, Studjum and Schenie (rather than Patient, Studium, Genie).

Oskar Panizza

Autobiography

translated by James J. Conway

Oskar Panizza, writer, born 12 XI 1853 in Bad Kissingen, comes from a family with a history of mental illness. Uncle suffered from partial religious insanity and died after spending 15 years in the mental ward of the Würzburg Juliusspital. Another uncle committed suicide at a young age. One aunt died of a stroke, another aunt is still alive, psychologically peculiar, partly witty, partly insane. All of these degrees of kinship relate to the maternal side. Mother still alive, an angry, energetic, strong-willed person of almost male intelligence. Father died of typhus, was of Italian descent, a passionate, dissolute, angry and clever man of the world, a bad family man. Of the patient’s siblings the two younger ones, like the patient himself, were subject to incidents of melancholy in earlier years. Younger sister attempted suicide twice (perhaps complicated by hysteria). There is prevailing mental activity throughout the family with a tendency to discussion of religious questions. Mother and patient writers. Patient himself suffered from the usual teething troubles, measles, whooping cough, found it very difficult to read, showed no talent, was nicknamed ‘the fool’ by his siblings, progressed with difficulty through high school, with his fruitless, exuberant imagination and constant self-absorption preventing him from grasping the need for regulated, systematic preparation for a profession in life, turned temporarily to music and finally graduated from the classical grammar school at an advanced age, 24 years old. While ill with measles, he had a slight somnambulistic attack at the age of about 12; he left his bed unconscious during the day, ran around the sick room and was finally found kneeling at his bed praying, and rescued from his trance. After graduating from high school, he turned to medical studies with great love and zeal, became co-assistant to Ziemßen, worked under the same at the clinical institute, received his doctorate summa cum laude in 1880 and began his apprenticeship that same year. As a student he became infected with syphilis, which, although treated lege artis for years, is still manifest today in the form of a powerful bud on the right tibia which defies the most energetic treatment by iodide of potassium. After completing his military service as a junior physician in the military hospital and being appointed assistant physician 2nd class in the reserve, patient went to Paris, provided with numerous recommendations by Ziemßen, but visited only a few hospitals and instead decided to study French literature, especially drama, for which he was particularly suited thanks to the knowledge of the French language which had always been cultivated in the childhood home as a result of his mother’s Huguenot descent. Returning to Munich in 1882, he entered the Oberbairische Kreis-Mad Asylum under Gudden as 4th assistant physician and served there for two years, advancing to 4th (?) assistant physician. Impairment of his health as well as scientific and other differences with his superior led him to leave this position in 1884 and at this point, apart from some minor temporary medical services as a general practitioner, he devoted himself entirely to literature, which had been on his mind since Paris. Still feeling some after-effects of a depression of the temper which occurred in the insane asylum and lasted for almost a year, he wrote the lyrical book of verse Düstre Lieder [Gloomy Songs] (Leipzig 1885), which was influenced by Heine. Uplifted and refreshed by this literary relief, he visited England in the same year, which was preceded by an intensive study of the English language and literature under Mrs. Callway, and he spent a full year engaged in literary activities at the British Museum. Londoner Lieder [London Songs] (Leipzig 1887) was written as a result of this stay. In the autumn of 1886, after a temporary stay in Berlin, return to Munich, in 1888 poems published as Legendäres und Fabelhaftes, [Legendary and Fantastical], some of which were the fruit of his preoccupation with old English ballads. In the following years learning and study of the Italian language and literature under Sgra Luccioli in Munich, as intensive involvement with foreign languages and literary productions turned out to be the best means of discharging all kinds of psychopathic impulses. Repeated trips to Italy. From 1890 onwards, as a result of acquaintance with M. G. Conrad, a series of essays, partly scientific, partly literary and artistic, appeared in the Gesellschaft, of which M. G. Conrad was the founder and director. In 1899 Dämmerungsstücke [Twilight Pieces], a collection of fantastical short stories, some of which were influenced by the American writer Edgar Poe, had already appeared. Through M. G. Conrad introduced to the Society for Modern Life in Munich; patient gave a number of lectures there, including ‘Schenie und Wahnsinn’ [Genius and Madness] (Munich, Pößl 1891), which attracted the attention of the authorities, the hostility of the ultra-montane press, resulting in ‘Sozialdemokraten im Frack’ [Social Democrats in Tails] and remonstrations of the Landwehr district command. Requested by the command to resign from the Society for Modern Life, patient refused and as a result was dismissed from a military relationship in which he had in the meantime advanced to assistant physician 1st class, with ‘a simple farewell’.

An essay by the patient ‘Das Verbrechen in Tavistock Square’ [‘The Crime in Tavistock Square’], recalling his time in England, appeared in the Sammelbuch der Münchner Moderne [Anthology of Modern Munich] (Munich, Plößl, 1891) and led to a judicial charge of ‘offences against morality’, which was nonetheless dismissed by the criminal chamber of the District Court of Munich I. In 1892 the tragic, humorous Aus dem Tagebuch eines Hundes [From a Dog’s Diary] was published, illustrated by Choberg in Leipzig. The following year Visjonen [Visions], a collection of short stories, again partly in the fantastical style and outlook of Edgar Poe. In 1893 Die unbefleckte Empfängnis der Päpste [The Immaculate Conception of the Popes] (Zurich, Schabelitz) appeared, a theological attempt to extend the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary by Pius IX in 1894 to the popes with all due embryological, anthropological and theological consequences, which was executed in an ostensibly most serious style and which according to the title page the patient had translated from Spanish. This writing was confiscated by court order as a result of a denunciation in Stuttgart and in so-called ‘objective proceedings’ banned throughout the German Empire. This was followed by harsh criticism from the Catholic and Protestant ecclesiastical press as well as public warnings against purchase. In 1894 Der teutsche Michel und der römische Papst [The German Michel and the Roman Pope] appeared with a foreword by M. G. Conrad, in which the gravamen of Germany against Rome were tendentiously summarised in the form of theses, but based on historical information and with extensive references to sources. This work was also confiscated in ‘objective proceedings’ in 1895, that is, after the expiry of the period in which charges and prosecution might be brought. In 1894 there was also Die Himmelstragödie das Liebeskonzil [The Tragedy of Heaven, the Love Council] (Zurich, Schabeliz), in which, in accordance with a quotation by Ulrich von Hutten, syphilis appeared in Italy at the end of the 15th century; based upon the depraved escapades at the papal court of Alexander VI it is executed in the form of a medieval mystery play under modern lighting. This book drama brought the patient to the (!) Munich Assizes in the spring of 1895, where he was sentenced to one year in prison under Par. 166 of the Reich Penal Code, a verdict that was upheld by the Imperial Court in Leipzig soon after. The patient served his sentence in the Amberg prison, where the defence counsel’s subsequent assertion of an objection on the basis of mental illness (without questioning the prisoner) was followed by a summary examination of same quoad psychen intactam – ‘Are you mentally ill?’ – ‘No.’ – which produced a negative result. After serving his sentence, patient farewelled Munich with the small brochure ‘Farewell to Munich’ (Zurich 1896), which resulted in confiscation and a warrant for prosecution of the author, who had in the meantime moved to Zurich. That same autumn the patient published the moral history Die bayrischen Haberfeldtreiben [The Bavarian Haberfeldtreiben; a form of informal moral court] (Berlin, G. Fischer), in which, at the request of the anxious publisher, some passages of the text as well as some verses of the ‘Haber Protocols’ originally appended to it, which the patient had published a few years earlier in an article for the Neue Rundschau (by the same publisher) without objection, were replaced by dots in the typeset which was already ready for printing.

Patient had meanwhile given up Bavarian indigence with the intention of acquiring Swiss citizenship after spending two years in Zurich. In the following year, with Schabeliz now also causing difficulties in Zurich, patient founded his own publishing house under the title of the journal established at the same time, Züricher Diskussionen, and published Dialoge im Geiste Huttens [Dialogues in the Spirit of Hutten], which was written in the prison in Amberg, which sought to discuss public conditions in the fresh and uninhibited style of early XVI century polemics. In the following spring of 1898 patient wrote the political satire Psichopatia criminalis (Zurich, Verlag Zür. Diskussionen) about his persecution at the hands of the German public prosecutors, satirised as suffering their own political insanity, one which had gripped the German public. (Wrong syntax!) It was followed by the drama Nero based on purely historical studies (Zurich 1898). In the same late autumn, patient was ostensibly charged with intercourse with a puella publica who had just reached the age of 15 – in Switzerland, sexual intercourse with girls under the age of 15 is a criminal offence, and by popular decree, the toleration of prostitution in the canton of Zurich was abolished – expelled by the police, branded as a ‘dirty individual’ in Swiss papers, and at the same time informed at the Zurich police headquarters that his expulsion from the canton of Zurich was extended to the whole of Switzerland. Patient responded to this act of violence in the next issue of the Züricher Diskussionen with open, unreserved disclosure of the facts, which exposed himself and the wrong he had committed, but at the same time pointed to the highest authority in Berlin, whose influence the patient believed to have discerned in the whole process. In Paris, where the patient had now settled, the Züricher Diskussionen, despite its now contradictory local title, continued in an intensified tone, especially in the political field, and around Christmas of the following year the fruit of a most withdrawn life and the freshest, finest and most immediate impressions of the French capital emerged, the collection of poems Parisjana, in which the personal adversary of the author, Wilhelm II, is portrayed as the public enemy of mankind and its culture, and where the line of thought and form of expression were exploited to the utmost aesthetic limit. As predicted, this writing was confiscated in Germany and a new warrant issued against the author, but at the same time what could not have been foreseen was that his assets, which had been pawned in Germany, were confiscated under the most twisted motivation – that he had fled. After a year of perseverance in the most distressing conditions, patient was forced to surrender to the court that issued the warrant, Munich – April 1901 – was imprisoned here, then after four months transferred by order of the Criminal Chamber to the Upper Bavarian Insane Asylum for six weeks with the aim of examining his mental state, and then released a few weeks after his return to prison with no notification of a court order. According to newspaper notes and a verbal statement to a private person by the first public prosecutor at the Munich I district court, Baron von Sartor, which could not be verified, the case of mental illness against the patient was suspended in response to the expert opinion of the Senior Physician of the Munich District Insane Asylum, Dr. Ungemach. After returning to Paris, patient published several more issues of Züricher Diskussionen (up to no. 32) and then, from November 1901, in the absence of a printer discontinued his journalistic activities, if not his writing activities. – In November 1903, the patient, who lived in the most absolute seclusion, was subject to a sequence of harassment which, given the extent of the operation (quere-la?), indicated the cooperation of a large number of detectives. And since the French government had exhibited, if not exactly benevolence, at least no form of hostility towards the patient, this was almost certainly the work of foreign detectives or a command issued in another country to disrupt the life of the patient through French private detectives recruited locally. Since, as already mentioned, he had not published anything for two years, there was always the possibility that another party, which was even less (!) disposed to the views of the patient, would be secretly monitoring his manuscripts, perhaps copying them and, if they corresponded to the views of this new party, ultimately publishing them, in the end even using the title, company, print and paper of the Züricher Diskussionen. This is the only way to explain the new hostilities against the patient, who at any rate was taken to be the author and responsible editor of the supposed publications. This was because the patient was even less inclined to believe that anyone in his proximity, Frenchman or foreigner, would have ever considered him to be anything other than entirely mentally sound, than the declaration of insanity made two years earlier in Munich would ever be taken seriously, such that any political party either favourable or hostile would have been disinclined to concern themselves with his manuscripts. The harassment, however, essentially consisted of minor things, such as extinguishing the hearth fire, clogging the fireplace, cutting off the water, damaging the apartment locks (!!), in sophisticated whistling intended to cause the most excruciating damage to the nervous system, molesting the auditory nerves with the most sensitive instruments, which sometimes came from a house opposite in the rue des Abbesses, sometimes on the street, and even here and there in the forest of Montmorency, where patient regularly went every Sunday. The simple fact that the whistling stopped the moment patient covered his ears, which would certainly not have been the case had it been of cerebral origin, indicated that these were no auditory delusions. Later in Munich, where the whistling that the patient regarded as directed against himself continued, it was confirmed by the unimpeachable witnesses Ludwig Scharf and the Comtesse zu Reventlow, with only its interpretation at times called into question. But in regard to the latter this was scarcely likely to be a case of misinterpretation after a ¾ year of sufferance and perseverance. – In addition to these attacks, which were carried out with the utmost precision, there seemed to be a smaller, less hazardous operation being carried out, this one in the immediate vicinity and in the subordinate hands of concierges or femmes de chambre (syntax!) – an operation that no ageing bachelor could elude – that of the marriage of the patient. As soon as he detected the operation, he quickly dealt with the local gossip and wrote to his mother, who lived in Munich, whose links to certain Parisian circles could not be dismissed out of hand, to say that given the current financial situation of her son, marriage was out of the question, that he had neither the inclination nor the time for marriage, and that he certainly would not – if the whistling and other harassment reported should ultimately be related to this project, which in fact struck himself as almost impossible – allow himself to be forced to choose a spouse by such ignoble means. The matrimonial intriguers fell away in response to this, while the other molestations continued. Since the former came to light again later in Munich, in the most grotesque and bizarre form, it must be mentioned that the patient had concealed the most serious reasons against entering into a marriage in his letter to his mother for reasons of consideration and propriety. The history of mental illness on his mother’s side, which was not to be dismissed, the syphilis which was still manifest in the form of a bud on his tibia dextra would today, when the statutes seek to prevent the mentally ill, the consumptive and the syphilitic from entering into matrimony, be considered a crime, a flippant means of producing decrepit offspring. In addition, the practice of his literary activity required the patient to spend the greater part of the day in absolute solitude and seclusion, in good weather on long lonely walks, habits that are certainly incompatible with marriage. And even if the products of this literary activity should be tarnished by the public or critics, for the patient they are not the expression of a whim or caprice, but an absolute necessity for relieving the brain. So he must take the safe route and maintain his psychic equilibrium, advance further along the old, tried and tested track, and not chase after fantasies which, although they appear highly expedient to those concerned, strike him as a danger to his health.

After more than six months of the molestation described above, which ultimately confined the patient to his apartment in the middle of summer and made him forego the necessary exercise in the fresh air, and after intensive occupation with scientific work failed to provide the necessary distraction, he made up his mind to depart without warning and on 23 June left Paris on the evening express train from the Lyon station and arrived in Lausanne (Switzerland) via Dijon the following noon. To his great astonishment, the whistling was also to be heard in Lausanne, if not at all to the same extent. The inevitable conclusion was that Paris was not the only source of hostility against the patient. The real reason for these manifestations remained concealed from him. He largely recovered on Lake Geneva and in the surrounding forests, where, unlike Paris, he was never bothered, but as the attempt to find a modest country apartment failed, after eight days he continued his travels to Munich via Bern, Zurich and Lindau. Since the molestations began here too, he presented himself to the Munich District Insane Asylum with a request for admission to furnish himself and others with evidence that he had not erred in his view that this was a matter of external, planned hostilities against himself; but he was rejected, allegedly because of overcrowding. He was persuaded by the director Vokke to enter the private insane asylum in Neu-Friedenheim. But the realisation that he was being harassed in unmistakable fashion led to a severe argument with the director, Dr Rehm, in the course of which the latter asked the patient to leave the institution. Patient then rented a modest room at Feilitzschstrasse 59/II (right), waiting to see what would come. During the ensuing ¼ year July to October patient completely avoided the city, assiduously walking in the Englischer Garten and surrounding areas, and with the onset of the adverse season visiting the State Library in the mornings, but in all other respects remaining entirely reserved and passive, recognising that a change in his external conditions could only be occasioned by his opponents rather than himself (?). His literary works in prose and bound form, which were created on his travels and in Munich and which are quite extensive, would not, unless the patient is most mistaken, be judged as pathological expectorations by any literary or psychiatric expert. Conditions were aggravated to the extent that now, in contrast to Lausanne and even Paris, severe harassment persisted at night through long-range pipes and flutes of a metallic character with the most intensive affront to the auditory organ. With suicidal tendencies having manifested once before in Paris, once in Lausanne and once in Neufriedenheim, (!) on 9 October, in a seizure of desperation and hopelessness (!), following the rapid writing of a will, there began the execution of an intention to commit suicide by hanging in a secluded spot of the Englischer Garten. But at the last moment faint-heartedness spoiled the decisive jump from the tree that he had climbed and the patient, who had not consumed nourishment in 24 hours, returned to his apartment in the deepest shame. On 19 October patient resorted to a last remedy which was related to the previous, ridiculously stupid attempt, yet perhaps effective in its consequences. After he had been unmistakably whistled at six times that day on his way to the State Library and then on his lonely walk through Oberföhring and the surrounding area, he went home, stripped down to his shirt and, taking advantage of the mild weather, ran down Sterneck-Maria-Josefa-Strasse to Leopoldstrasse at five o’clock in the afternoon with the intention of being caught and apprehended on suspicion of being mentally ill and taken to a public institution and there examined by experts, thus achieving what he had had sought in vain three months beforehand in the Upper Bavarian insane asylum. This ruse was successful. Seized and led to the nearest house, he gave the policeman who had been summoned a false name, Ludwig Fromman, stenographer from Würzburg. An ambulance carriage was requisitioned and the patient taken to the police, where, after a brief examination by the district physician, he was transferred to the psychiatric ward of the I/J city hospital.

‘Autobiography’ by Oskar Panizza was written in German in 1904 (dated 17 November) as ‘Selbstbiographie’ and first published posthumously in In memoriam Oskar Panizza, Friedrich Lippert and Horst Stubbe (eds.) in Munich in 1926.

This translation © 2021 James J. Conway